2012/10/28

entretien avec pierre legendre

Juriste psychanalyste. Directeur du Laboratoire européen pour l'étude de la filiation. Agrégé de droit romain et d'histoire du droit. Promoteur d'une anthropologie dogmatique, il articule sa formation juridique avec une solide expérience psychanalytique.

Il est l'auteur d'une bonne trentaine d'ouvrages, parmi lesquels Sur la question dogmatique en Occident ; La Neuf Cent Unième Conclusion : étude sur le théâtre de la raison ; L'Empire de la vérité. Introduction aux espaces dogmatiques industriels; Le Crime du caporal Lortie. Traité sur le père ; De la société comme texte. Linéaments d'une anthropologie dogmatique. Tous ces livres sont publiés chez Fayard.

Dominium Mundi, Mille et une nuit, Paris, 2006 ; Vues éparses, Entretiens radiophoniques, Mille et une nuit, Paris, 2009.

Il a également réalisé deux films très remarqués : La Fabrique de l'homme occidental (1996) et Miroir d'une nation. L'Ecole nationale d'administration (2000), dont les textes sont édités aux éditions Mille et une nuits. Editeur chez lequel il a publié en 2002 et en collaboration Le Façonnage juridique du marché des religions aux Etats-Unis.

1

Le droit sert à tout et sert toutes les causes de tous ceux qui savent politiquement s'en servir.

Jouir du Pouvoir, Ed. de Minuit, Paris, 1976.

2

On ne dialogue pas avec la Loi, on la fait parler.

Ibidem

3

Entretien avec Pierre Legendre : "Nous assistons à une escalade de l'obscurantisme" *

"Vous avez consacré une grande part de votre énergie à rendre compte de la "construction anthropologique occidentale". Vous vous êtes interrogé, tout au long de votre œuvre, sur le sens des règles de droit et sur leur légitimité. Vous avez montré que l'Etat était jusqu'à présent le garant de la raison.

Ce qui s'est passé le 11 septembre (2001) à New York signifie-t-il qu'il ne l'est plus ?

- On ne peut pas imposer par la force ce qui doit être conquis. La démocratie a été une conquête en Occident, jusqu'au moment où elle s'est retournée en devenant la caserne libertaire. De mon point de vue, il y a connivence de fait entre l'idéologie libertaire et l'ultralibéralisme.

Figurez-vous qu'après la chute du mur de Berlin, Harvard Business Review a publié un article intitulé "La démocratie est inévitable". Désormais, on vous imposera la démocratie comme le business, y compris sur le mode de la menace. J'ai vu en Afrique les Etats potiches que nous avons fabriqués. Sans tradition administrative, ils ne pouvaient qu'être corrompus. Ainsi ai-je vu par exemple vendre des diplômes.

La doxa de l'ONU et de l'Unesco affirmait péremptoirement que partout où le progrès technique s'installerait, la religion se folkloriserait ou disparaîtrait. J'ai pensé qu'il fallait, au contraire, travailler à faire coexister l'éducation traditionnelle, y compris l'école coranique, avec l'enseignement moderne et prendre le temps de ce métissage. Aussi ai-je dit à l'un de mes mandants qui professait ces thèses : "A mon avis, l'islam reviendra, le couteau à la main." Nous y sommes. Les institutions démocratiques ne s'imposent pas, elles doivent être conquises par les Etats et par les sujets.

- Mais justement, chez nous, les jeunes générations ont-elles les moyens de conquérir ces institutions démocratiques ?

- Non. La débâcle normative occidentale a pour effet la débâcle de nos jeunes : drogue, suicide, en un mot nihilisme. Notre société prétend réduire la demande humaine aux paramètres du développement, et notamment à la consommation. L'an dernier, le PDG du groupe Vivendi a dit : "Le temps politique classique est dépassé ; il faut que le consommateur et les industriels prennent le leadership." Voilà l'abolition des Etats programmée.

- Vous rapprochez donc le jeune Occidental qui ne sait plus donner du sens à sa vie et l'islamiste qui s'abandonne à son fantasme de mort ?

- La souveraineté du fantasme appelle le nihilisme.

Dans Les Possédés de Dostoïevski, Kirilov se suicide pour prouver qu'il est à lui-même le principe de raison. En se tuant, il croit supprimer chez l'homme la souffrance et la peur, et prouver que l'humanité peut se surmonter elle-même, devenir Dieu.

Nous assistons à une escalade de l'obscurantisme. Voyez, aux Etats-Unis, ce que certains technocrates et universitaires appellent le transhumanisme, la post-humanité qui comporte la résolution intégrale du problème de la mort (sic). Freud avait bien aperçu le creuset délirant de la raison que les religions prennent en charge en métabolisant le meurtre.

Le meurtre habite l'esprit de l'homme. Dans l'entreprise, la concurrence est un meurtre transposé ; en politique, les élections le sont aussi : on renvoie son adversaire dans ses foyers. On ne rendra pas la vie supportable par des raisonnements scientifiques ou de bons sentiments, mais par des interprétations cohérentes qui peuvent exiger de chacun une part de sacrifice pour qu'on ne donne pas, par exemple, de leçons à autrui au nom de nos propres aveuglements.

- Comment le spécialiste du droit romain et du droit canonique que vous êtes a-t-il articulé son savoir avec la psychanalyse pour ouvrir le champ de cette "anthropologie dogmatique" qui structure votre travail ?

- Je me suis donné plusieurs formations. L'une d'elles, le droit romain et l'histoire du droit, a fait de moi un professeur agrégé d'histoire du droit en 1957. Les droits romain et canonique sont le cœur méconnu des sciences juridiques, qui contiennent les éléments refoulés de la construction de l'Occident.

La grande querelle de l'Occident romano-canonique chrétien avec la tradition juive est aux sources d'une conception religieuse et politique de l'Etat qui a retenu toute mon attention. Remarquez que l'étymologie du mot Etat implique en général un complément de nom (l'état de quelque chose) et évoque la station verticale. L'Etat est la construction normative, institutionnelle, qui fait tenir debout quelque chose d'essentiel à la vie sociale. Dans le même temps, je me suis donné une formation économique. J'y ai ajouté une formation littéraire qui incluait la philosophie, la sociologie et la morale. Etudiant, à la fin des années 1950, j'ai eu vent de l'existence de la psychanalyse. Bientôt, j'ai commencé à fréquenter un divan. La psychanalyse sentait le soufre et son usage était alors occulte. Enfin, la fréquentation des arts, et notamment de la poésie, m'était très chère.

- En quoi le droit romain nous concerne-t-il aujourd'hui ? Informe-t-il seulement notre corpus juridique ?

- Non, il explique aussi une grande part de la réalité sociale. Armature du christianisme, il est porteur de rituels, de liturgies, d'une certaine tolérance d'autres cultures, dont Justinien, au VIe siècle, précise remarquablement les limites : "Les juifs se livrent à des interprétations insensées."

- De votre point de vue, l'antijudaïsme chrétien qui a survécu jusqu'à nos jours, et a, en partie, fécondé l'antisémitisme raciste, tient-il sa puissance du droit romain ?

- La tragédie ultime du XXe siècle, la Shoah, suppose des siècles et des siècles de haine. Je suis un homme du passé et de l'avenir lointain. Je n'habite pas le présent, car j'ai compris la nécessité de combattre la mémoire courte. J'ai vécu avec des hommes du texte, ces médiévaux pour qui l'historique est une affaire géologique, sédimentée : le passé est toujours là, présent, et le futur est là, devant nous.

Le mot antisémitisme est récent. Dans ma plongée dans les littératures latines de chancellerie, j'ai été frappé par la violence antijuive de certains textes pontificaux du XIIIe siècle. Le pontife romain se considère aussi comme le pape des juifs et stigmatise la circulation d'interprétations non conformes des textes sacrés par les rabbins. Le système romano-chrétien évacue la circoncision malgré la matrice biblique, mais le corps, refoulé par le christianisme, revient sous la forme du centralisme papal. On disait autrefois de l'empereur romain qu'il avait "tout le droit dans l'archive de sa poitrine": la corporéité de la lettre s'incarne dans l'empereur, puis dans le pape, interprète unique et souverain de la parole.

- Comment ne pas penser à la façon dont Ernst Kantorowicz a fait du souverain l'énonciateur de la loi, le corps du pouvoir. Est-ce dans la même perspective que vous montrez que le corps ne se réduit pas au biologique, que, chez l'homme, la vie de la représentation prime sur la vie animale et qu'il n'y a pas de corps sans fantasme du corps ?

- J'ai correspondu avec Kantorowicz. J'ai fait traduire ses articles aux Presses universitaires de France. L'anthropologie travaille à la fois l'image, le corps et le mot. Comme lui, je pense que la modernité commence au XIIe siècle avec le Moyen Age classique, quand le christianisme latin s'est approprié le legs historique du droit romain en sommeil depuis plus de 500 ans.

Ce fut le début de l'Etat moderne, qui bat aujourd'hui en retraite sous les coups de l'affirmation de l'individu. Et les Etats contemporains se lavent les mains quant au noyau dur de la raison qui est la différence des sexes, l'enjeu œdipien. Ils renvoient aux divers réseaux féodalisés d'aujourd'hui l'aptitude à imposer législation et jurisprudence.

Pensez aux initiatives prises par les homosexuels. Le petit épisode du pacs est révélateur de ce que l'Etat se dessaisit de ses fonctions de garant de la raison. Freud avait montré l'omniprésence du désir homosexuel comme effet de la bisexualité psychique. Un exemple de transposition culturelle : le rituel monastique qui chante Jésus en l'appelant "notre Mère". La position homosexuelle, qui comporte une part de transgression, est omniprésente.

L'Occident a su conquérir la non-ségrégation, et la liberté a été chèrement conquise, mais de là à instituer l'homosexualité avec un statut familial, c'est mettre le principe démocratique au service du fantasme. C'est fatal, dans la mesure où le droit, fondé sur le principe généalogique, laisse la place à une logique hédoniste héritière du nazisme.

En effet, Hitler, en s'emparant du pouvoir, du lieu totémique, des emblèmes, de la logique du garant, a produit des assassins innocents. Après Primo Levi et Robert Antelme, je dirai qu'il n'y a aucune différence entre le SS et moi, si ce n'est que pour le SS le fantasme est roi. Le fantasme, comme le rêve qui n'appartient à personne d'autre qu'au sujet (personne ne peut rêver à la place d'un autre), ne demande qu'à déborder.

La logique hitlérienne a installé la logique hédoniste, qui refuse la dimension sacrificielle de la vie. Aujourd'hui, chacun peut se fabriquer sa raison dès lors que le fantasme prime et que le droit n'est plus qu'une machine à enregistrer des pratiques sociales.

- Votre passage par l'Afrique a joué un grand rôle dans votre conception du droit. Il vous a permis de relativiser nos valeurs occidentales et de lire, partout dans le monde, ce dessaisissement d'un Etat instituant. Vous y avez observé les édifices institutionnels par lesquels des sociétés comme la nôtre répondent à l'angoisse existentielle.

- J'ai travaillé au Gabon avec une entreprise qui vendait du développement, avec les Nations unies au Congo ex-belge, puis au Mali avec l'Unesco. J'ai compris que ma formation de juriste préoccupé des textes du Moyen Age m'était bien plus utile que les sciences économiques.

Je voyais, en effet, dans les écoles coraniques des enfants réciter rituellement des versets dans la langue sacrée du Coran, qui n'était pas la leur, exactement comme les glossateurs médiévaux transmettaient en latin le droit romain disparu.

Je découvrais l'égalité de tous devant la vie de la représentation : l'Etat occidental n'est qu'une forme transitoire de cette vie. Il reproduit du sujet institué, en garantissant le principe universel de non-contradiction : un homme n'est pas une femme, une femme n'est pas un homme ; ainsi se construisent les catégories de la filiation.

La fonction anthropologique de l'Etat est de fonder la raison, donc de transmettre le principe de non-contradiction, donc de civiliser le fantasme. L'Etat, dans la rationalité occidentale, est l'équivalent du totem dans la société sans Etat. En Afrique, il y a aussi un au-delà de l'individu qui est peut être en train de se perdre chez nous."

* Propos recueillis par Antoine Spire, Le Monde 23 octobre 2001, p. 21, LE MONDE | 22.10.01 | 11h55

Jurisdiction in Deleuze by Edward Mussawir

Jurisdiction in Deleuze: The Expression and Representation of Law explores an affinity between the philosophy of Gilles Deleuze and jurisprudence as a tradition of technical legal thought. The author addresses and reopens a central aesthetic problem in jurisprudence: the difference between the expression and the representation of law. Deleuze is taken as offering not just an important methodological recovery of an ‘expressionism’ in philosophy – specifically through Nietzsche and Spinoza – but also a surprisingly practical jurisprudence which recasts the major technical terms of jurisdiction (persons, things and actions) in terms of their distinctively expressive or performative modalities. In paying attention to law’s expression, Deleuze is thus shown to offer an account of how meaning may attach to the instrument and medium of law and how legal desire may be registered within the texture and technology of jurisdiction.

Hatred of Democracy by Jacques Rancière reviewed by Paulina Tambakaki

Although democracy has always been hated, the anti-democratic sentiments

of today, warns Rancière, have taken a worrying turn. It is a worrying

turn because alongside the discourse which deplores democracy for its

limitlessness, for the atomism and unfettered consumerism of democratic

society, there is another discourse which suggests that democracy is

only good when spread abroad to defend the values of civilisation. For

most of his book Rancière persuasively challenges this latest expression

of anti-democratic sentiment, and he confidently argues that behind

this new hatred of democracy are entrenched forms of domination,

oligarchies of power and wealth, which no longer tolerate limitations to

the growth of their authority. These oligarchies, he stresses, have

inverted democracy as a term. By reducing it to mass individualist

society, they charge democracy with social homogenisation - much like

totalitarianism - and with collapsing government into the limitless

demands of society. Rancière is not disillusioned about present-day

democracy, to be sure, and yet for him democracy denotes something

different. As the very principle of politics, democracy steers towards a

redistribution of lots and an overthrowing of places in society. For

Rancière it involves a struggle, a movement to displace limits, and he

concludes that in resisting this movement present-day anti-democrats are

erasing politics.

athenian democracy

the modern word

'idiot' finds its origins in the ancient Greek word ἰδιώτης, idiōtēs, meaning a private person who is not actively interested in politics. According to Thucydides,

Pericles may have declared in a funeral oration: We do not say that a man who takes no interest in politics is a man

who minds his own business; we say that he has no business here at all.

Paragrana

"Paragrana" is an international journal of historical anthropology. It

is dedicated to the continuing study of phenomena and structures of

human conduct after the collapse of an obliging abstract anthropological

norm. The area of contention between history, anthropological critique,

and the humanities is researched and questions are asked which make

these studies productive for new kinds of paradigmatic exploration.

get the magazine

get the magazine

2012/10/26

the first traces of hands impressed in rock

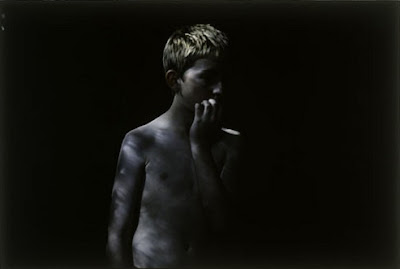

What do we seek, since the first traces of hands impressed in rock the long, hallucinated perambulation of men across time, what do we try to reach so feverishly, with such obstinacy and suffering, through representation, through images, if not to open the body’s night, its opaque mass, the flesh with which we think – and present it to the light, to our faces, the enigma of our lives.

1. Philippe Grandrieux, ‘Sur l'horizon insensé du cinéma’, Cahiers du cinéma hors série: Le siècle du cinema (November 2000).

1. Philippe Grandrieux, ‘Sur l'horizon insensé du cinéma’, Cahiers du cinéma hors série: Le siècle du cinema (November 2000).

Peter Matussek - The Renaissance of the Theater of Memory

Giulio Camillo (1480 - 1544) was as well-known in his era as Bill Gates is now. Just like Gates he cherished a vision of a universal Storage and Retrieval System, and just like Microsoft Windows, his ‘Theatre of the Memory’ was, despite constant revision, never completed. Camillo’s legendary Theatre of Memory remained only a fragment, its benefits only an option for the future. When it was finished, the user - so he predicted - would have access to the knowledge of the whole universe. On account of his promising invention, Camillo’s contemporaries called him ‘the divine’. For others, like Erasmus or the Parisian scholars, he was just a ‘quack’, but also this only shows that his reception was as strong as is the case with the computer gurus of our days. Still, Camillo was forgotten immediately after his death. No trace is left of his spectacular databank - except a short treatise which he dictated on his deathbed and which was formulated in the future tense: ‘L’Idea del Theatro’ (1550).

It was only in the computer age that Camillo’s name reappeared out of oblivion - at first sporadically in a few specialised articles in the fifties, then with increasing intensity and enthusiasm, until Camillo became a real hero of books and congresses, and even of television programmes[1] and Internet appearances[2] . How did the renaissance of this Renaissance encyclopaedist come about?

The catalyst was a chance occurrence: Ernst Gombrich, the director of the Warburg Institute in London gave Camillo’s treatise to his colleague Frances Yates to read. She studied this short work thoroughly and was so fascinated that she not only brought the ‘Theatro’ back to life in her mind’s eye, but also made a reconstructional drawing of it in accordance with Camillo’s instructions. The result formed the basis of a book on the history of the art of memory, which became one of the most influential works of cultural studies of recent decades.[3] Further attempts at a reconstruction followed that of Yates, and their variety demonstrates how little we know about Camillo.

The objective knowledge we do have can be summarised very briefly. The structure was a wooden building, probably as large as a single room, constructed like a Vitruvian amphitheatre. The visitor stood on the stage and gazed into the auditorium, whose tiered, semicircular construction was particularly suitable for housing the memories in a clearly laid-out fashion - seven sections, each with seven arches spanning seven rising tiers. The seven sections were divided according to the seven planets known at the time - they represented the divine macrocosm of alchemical astrology. The seven tiers that rose up from them, coded by motifs from classical mythology, represented the seven spheres of the sublunary down to the elementary microcosm. On each of these stood emblematic images and signs, next to compartments for scrolls. Using an associative combination of the emblematically coded division of knowledge, it had to be possible to reproduce every imaginable micro and macrocosmic relationship in one’s own memory. Exactly how this worked remains a mystery of the hermetic occult sciences on which Camillo based his notion.

However, what makes Yates’ study so fascinating is not so much her attempt to unveil the mystery - because this has since been disputed in further research - but a much bolder hypothesis which she advanced only in a cautious aside: the essential connection between this Renaissance scholar’s combinational data construction and the operation of today’s digital calculator. This hypothesis met with general approval. Umberto Eco labelled Camillo as a cabbalistic programmer[4] , Lina Bolzoni called his data construction the ‘ultimate computer’[5] , Hartmut Winkler derived an entire media theory from ‘L’Idea del Theatro’[6] and Stephen Boyd Davis considered it to be the historical forerunner of the design of a virtual reality.[7]

But are we not doing Camillo’s ominous theatre an injustice by equating it with the Docuverse of the computer age?

One argument for the historical connection is that, for some time now, we have been able to observe a shift in the prevalent model of human as well as digital memory: from a repository to a theatrical stage.[8] Memories no longer seem to us to constitute a passive inventory for deposit and withdrawal; rather, they seem far more like actors in a succession of changing stage settings. A telling metaphor shift in the neuro-sciences goes hand in hand with corresponding changes in the ways we speak about computers. In the wake of advances in interactive applications, the function of digital technology is no longer described merely in terms of "storage and retrieval," but rather in terms of the performativeness of images in motion.

In this connection, one of the most influential books about contemporary computer interface design is entitled "Computers as theatre"[9] ; but its author, Brenda Laurel, was not the first one to propagate this new way of looking at computers. The history of the newer interface technology similarly begins with the "Spatial Data Management System", that was developed in the late 1970s by Richard Bolt and Nicholas Negroponte at the MIT.It allowed the user, sitting in a cockpit, to switch back and forth between different screens whose contents he could zoom toward or away from, creating the impression of navigating through a "dataland."[10]

This new interface put to new use an old insight of the Roman rhetoric manuals – namely, that the highest degree of mnemonic efficiency is exhibited by techniques involving topographical arrangements of mental images (loci et imagines). As Richard Bolt states: "Intrinsic to the ensemble of studies outlined in the proposal was a study recalling the ancient principle of using spatial cueing as an aid to performance and memory." He called it the "Simonides Effect"[11] , alluding to the Greek poet Simonides of Keos, to whom the Roman rhetoricians attributed the invention of the ancient art of memory. The Macintosh User Interface is, as Nicholas Negroponte has implied, also based on this sort of Simonides Effect.[12]

It is true that the Human Interface Guidelines,[13] which were developed by Apple's Human Interface Group during the eighties, could well have been borrowed from the traditional teachings of rhetorical ars memoria. In addition to the basic "See-and-Point" principle, which recalls the ancient loci et imagines, the most important key words in the Guidelines are "Feedback and Dialogue", "Consistency" and "Perceived Stability". In the Rhetorica Ad Herennium we read that rote learning is most effective "when we [employ] not mute and indistinct images, but rather ones that set something in motion" (Apple's "Feedback and Dialogue"); these actuating images (imagines agentes) must be "arranged at certain fixed locations" (Apple's "Consistency"); and finally, says the Rhetorica, there must be no opportunity for us to "accidentally be mistaken in the number of locations" (Apple's "Perceived Stability").[14] Psychological studies in the workplace have confirmed that these principles considerably increase the ease with which the use of operating systems and software applications is learned.[15]

It is evident that, considering the explosion in user-designated storage options, the particular architecture of memory suggested by the desktop metaphor will have been put out of joint. And if we stick to the terms of our historical analogy, we might say that the current situation corresponds to the phase in which the classical memory palaces of antiquity gradually collapsed under the pressure of increasing amounts of amassed knowledge.

This is precisely the situation in which Camillo found himself with regard to the scholastic treatises of the Middle Ages: They curbed the remnant of a productive imagination in images from the memory in favour of a mechanical rote learning of prayers, virtues, and lists of mental objects.[16] It is here that Camillo comes in with his attempt to reanimate the now mechanical and uncreative memoria. He reminded his contemporaries that the function of imagines agentes was not just the "painting of an entire scene”,[17] but rather the stimulation of imagination through their agency. Camillo expressly emphasizes the matter that concerns him: "to find, in these seven comprehensive and diverse units, an order that keeps the mind keen and shakes up the memory."[18]

So these images from the memory were no longer purely a means of better remembering, but a medium for better concentration to the benefit of empathic recollection. For this purpose, he transplanted the arena of ars memoria from the traditional treasuries (thesauri) and palaces of memory to the Vitruvian theatre. The "drama" that he produced on this stage made use of the teachings of antiquity, but dressed them up in hermetic, cabbalistic costume.

But Camillo also departed from the tradition in one other aspect, in that he reversed the topography of structure of neo-classical theatre. With this inversion, the efficiency of the ancient architecture of memory could be significantly increased. Its user could navigate through the three-dimensional arrangement of his own will and vary his view between near and far accordingly.

No doubt there is a structural affinity between such ideas and the digital theater of memory. For some years now, there has been work on 3D visualisation processes: vector-driven cartographies such as Hyper-G, VRML, Hyperbolic Tree, Hotsauce, Flythrough, etc., which alter the depicted space with every movement of the mouse, joy stick or data glove. Such means are also used to attempt to increase the number of memory locations without creating disorientation.

But how is this related to the cosmological context in which these ideas were valid? Is this not entirely different from the post-metaphysical situation of memory architecture? Remarkably enough the opposite is true, because today's technology produces similar effects: The "Pan-Mnemism"[19] of our time is nourished by the dream of a universal, encyclopaedic machine. The hypertext guru Ted Nelson, for example, has something comparable in mind:

"Universal or grand hypertext […] means […] an accessible great universe of linked documents and graphics […]. This is an idea many people now share – the idea that we can get to everything, add to everything, keep track of everything, tie everything together, that we can have it all."[20]

What is at stake here is no longer merely the retrieval of profane information, the functional organization and recall of locations in the memory, but the spellbinding attraction of a fantasy of omnipotence: having the sum total of the world's knowledge at one's disposal – a move that his patron, the King of France, surely appreciated. And not only that: the spiritual inclinations of times past also make their reappearance in the digital theatre of memory. Brenda Laurel says:

"[...] for virtual reality to fulfill its highest potential, we must reinvent the sacred spaces where we collaborate with reality in order to transform it and ourselves."[21]

Now, it is in the nature of the dream of a total encyclopaedia that it must remain a dream. In this respect, it is worth noting that Camillo's Idea del Theatro was formulated in the future tense – as if the actual theatre of memory was still to be built. Unfinishability is here no shortcoming, but rather an added value; it does not diminish, but rather intensifies the mystery. The World Wide Web also owes its aura as a pan-mnemistic docuverse to the sfumato of a diffuse presentation of data, whose incompleteness stimulates us to act on hunches and intuitions, and thus produces that feeling of exuberant spatial experience with which passionate web-surfers are filled. The necessarily limited frame of the monitor only augments this experience by its peephole effect; it feeds the voyeuristic fantasy that there is still something infinitely more thrilling to discover than what is actually before one's eyes.

Nevertheless, what differentiates Camillo from today's cybernauts and sheds light on the possibly untapped potential of the digital theater of memory is the fact that his data construction always appears as theatre. The sites and images of his model are not meant to fascinate in an unmediated way, but should rather be reflected on as staged objects.

In contrast, the technical #movement# of images by means of computer animation does not lead to #an activity of# reflection but is perceived passively, in a reflex-like manner; instead of shaking up the memory, it conditions it. Camillo's theatre presents itself as an enclosed space, and, precisely for that reason, incites one to transcend it. On the other hand, the forms of 3D visualization, which give the illusion of endless space, prevent the data-traveller from realizing that the trajectory of his transit is fixed and thus undermine the desire for transcendence. This is because our imaginative activity diminishes in direct proportion to increased activity on the screen.

What is decisive to this difference is not the outer but the inner movement. In computer animation it is directed unambiguously at the consumption of an object; in Camillo’s work, however, the self-reflexive contemplation of the object by a subject also involves a rebound movement back to the subject. This reflexivity is made evident in Camillo's inversion of the theatre structure, which places the objects of memory in the tiers, where they simultaneously return the gaze of the observer while he stands on the stage and constitutes the centre of intellectual activity.

But why would this turnaround not also make Camillo's memory theatre a viable model for turning the digital staging of information into a self-reflective form?

Indeed, in recent years, there have been several artistic attempts to play upon Camillo’s idea. They indicate that an anamnesis of computer-presented data is not encouraged when the interface vanishes, as if it disappeared by immersion under the surface of the water, as is postulated by today’s pioneers of Interface Design, but rather, on the contrary, when the surface is mirrored back to the observer.

Once again, the idea for this comes from Yates’ #study#. Robert Edgar drew Bill Viola’s attention to the book and from then on Viola proclaimed Camillo the forerunner of digital ‘data space’.[22] It was on this basis that he produced his spatial installation ‘Theatre of Memory’ (1985), in which the processes of electrical connection in human memory are associated with the electronics of video. In the same year, Robert Edgar himself programmed his ‘Memory Theatre One’ on an ‘Apple II’, which used the then modest possibilities of computer graphics to reconstruct Camillo’s amphitheatrical data architecture. In the mid-nineties, Agnes Hegedus read this influential book together with her partner Jeffrey Shaw. She constructed a ‘Memory Theatre VR’ (1997), which used the new possibilities of computer simulation. On the inside walls of an accessible rotunda, which acted as a sort of ‘cave’, mobile panoramic images concerning the history of artificial memory were projected using a 3D mouse. And since 1998, the performance artist Emil Hvratin has carried out several projects in which the information scenarios of our era are questioned on the basis of Camillo’s work.

What do we learn from these reflections on the state of the computer age? To what extent do they give us a definite answer about the way information will be staged in the future?

As stated at the beginning, the Idea del Theatro is #has?# left much in the dark. Its "revelation" begins with a reference to the significance of silence in the face of divine secrets. And no doubt, Camillo's mystique only profited from the fact that he divulged just bits and pieces of information about how his theatre was made. Only as long as he continued to work on its expansion, to endeavour constantly to overhaul its architecture and iconology, could he have given himself and others the feeling of being on the trail of the secret of the alchemistic transformation of memory into recollection.

[1] Bolzoni, Lina: Il Teatro della Memoria; television film, 1990.

[2] Comp. the annotated list of links under www.sfb-performativ.de/seiten/b7_links.html.

[3] Frances Yates, The Art of Memory, London, 1996, p. 114 ff.

[4] Eco, Umberto: review of: Mario Turello, Daniele Cortolezzis: Anima Artificiale. Il Teatro magico di Giulio Camillo. in: L’Espresso, 14.8.1988.

[5] Bolzoni, Lina: The Play of Images. The Art of Memory from its Origins to the Seventeenth Century, in: Corsi, Pietro (ed.): The Enchanted Loom. Chapters in the History of Neuroscience, New York/Oxford, 1991, p. 23.

[6] Winkler, Hartmut [1994]: Medien - Speicher - Gedächtnis. Online: www.uni-paderborn.de/~winkler/gedacht.html.

[7] Davis, Stephen Boyd [1996]: The Design of Virtual Environments with particular reference to VRML. Online: www.man.ac.uk/MVC/SIMA/vrml_design/title.html.

[8] Cf. Bernard J. Baars, Das Schauspiel des Denkens, Stuttgart, 1998.

[9] Brenda Laurel: Computers as Theatre; Reading (Mass.) 1991.

[10] Richard A. Bolt: Spatial Data Management; Cambridge (Mass.) 1979, p.13.

[11] Ibid. 8.

[12] Nicholas Negroponte, Total digital. Die Welt zwischen 0 und 1 oder Die Zukunft der Kommunikation, Munich, 1995, p. 135 ff.

[13] Apple Computer Inc., Human Interface Guidelines: The Apple Desktop Interface, Reading (Mass.), 1987.

[14] Rhetorica Ad Herrenium III, XVIIf., Apple Computer p. 3 ff.

[15] Cf., e.g., Alexandra Altmann, "Direkte Manipulation: Empirische Befunde zum Einfluß der Benutzeroberfläche auf die Erlernbarkeit von Textsystemen," A&O: Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie 3 (1987): pp. 108-114.

[16] Cf. Frances Yates, The Art of Memory, London, 1966, p. 114ff.This does not contradict Horst Wenzel's observations on the participatory character of mediaeval memoria in: Horst Wenzel, Hören und Sehen. Schrift und Bild. Kultur und Gedächtnis im Mittelalter, Munich, 1995.

[17] Willhelm Schmidt-Biggeman, "Robert Fludds Theatrum memoriae," Ars memorativa. Zur kulturgeschichtlichen Bedeutung der Gedächtniskunst 1400-1750, eds. Jörg Jochen Berns and Wolfgang Neuber [Tübingen, 1993] p. 157.

[18] "la memoria percossa": 1550, p. 11.

[19] Elisabeth von Samsonow, "Zeit bei Giordano Bruno oder: Zum Verhältnis von Kosmochronie und Mnemochronie," eds. Eric Alliez et al., Metamorphosen der Zeit , Munich, 1999, p. 140.

[20] Cited in: Robert E. Horn, Mapping Hypertext: Analysis, Linkage, and Display of Knowledge for the Next Generation of On-Line Text and Graphics, Waltham, 1989, p. 259.

[21] Laurel, ibid. p. 196 ff.

[22] Bill Viola [1983]: Will There be Condominiums in Data Space? In: Ders.: Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House, London, 1995, pp. 98-111.

It was only in the computer age that Camillo’s name reappeared out of oblivion - at first sporadically in a few specialised articles in the fifties, then with increasing intensity and enthusiasm, until Camillo became a real hero of books and congresses, and even of television programmes[1] and Internet appearances[2] . How did the renaissance of this Renaissance encyclopaedist come about?

The catalyst was a chance occurrence: Ernst Gombrich, the director of the Warburg Institute in London gave Camillo’s treatise to his colleague Frances Yates to read. She studied this short work thoroughly and was so fascinated that she not only brought the ‘Theatro’ back to life in her mind’s eye, but also made a reconstructional drawing of it in accordance with Camillo’s instructions. The result formed the basis of a book on the history of the art of memory, which became one of the most influential works of cultural studies of recent decades.[3] Further attempts at a reconstruction followed that of Yates, and their variety demonstrates how little we know about Camillo.

The objective knowledge we do have can be summarised very briefly. The structure was a wooden building, probably as large as a single room, constructed like a Vitruvian amphitheatre. The visitor stood on the stage and gazed into the auditorium, whose tiered, semicircular construction was particularly suitable for housing the memories in a clearly laid-out fashion - seven sections, each with seven arches spanning seven rising tiers. The seven sections were divided according to the seven planets known at the time - they represented the divine macrocosm of alchemical astrology. The seven tiers that rose up from them, coded by motifs from classical mythology, represented the seven spheres of the sublunary down to the elementary microcosm. On each of these stood emblematic images and signs, next to compartments for scrolls. Using an associative combination of the emblematically coded division of knowledge, it had to be possible to reproduce every imaginable micro and macrocosmic relationship in one’s own memory. Exactly how this worked remains a mystery of the hermetic occult sciences on which Camillo based his notion.

However, what makes Yates’ study so fascinating is not so much her attempt to unveil the mystery - because this has since been disputed in further research - but a much bolder hypothesis which she advanced only in a cautious aside: the essential connection between this Renaissance scholar’s combinational data construction and the operation of today’s digital calculator. This hypothesis met with general approval. Umberto Eco labelled Camillo as a cabbalistic programmer[4] , Lina Bolzoni called his data construction the ‘ultimate computer’[5] , Hartmut Winkler derived an entire media theory from ‘L’Idea del Theatro’[6] and Stephen Boyd Davis considered it to be the historical forerunner of the design of a virtual reality.[7]

But are we not doing Camillo’s ominous theatre an injustice by equating it with the Docuverse of the computer age?

One argument for the historical connection is that, for some time now, we have been able to observe a shift in the prevalent model of human as well as digital memory: from a repository to a theatrical stage.[8] Memories no longer seem to us to constitute a passive inventory for deposit and withdrawal; rather, they seem far more like actors in a succession of changing stage settings. A telling metaphor shift in the neuro-sciences goes hand in hand with corresponding changes in the ways we speak about computers. In the wake of advances in interactive applications, the function of digital technology is no longer described merely in terms of "storage and retrieval," but rather in terms of the performativeness of images in motion.

In this connection, one of the most influential books about contemporary computer interface design is entitled "Computers as theatre"[9] ; but its author, Brenda Laurel, was not the first one to propagate this new way of looking at computers. The history of the newer interface technology similarly begins with the "Spatial Data Management System", that was developed in the late 1970s by Richard Bolt and Nicholas Negroponte at the MIT.It allowed the user, sitting in a cockpit, to switch back and forth between different screens whose contents he could zoom toward or away from, creating the impression of navigating through a "dataland."[10]

This new interface put to new use an old insight of the Roman rhetoric manuals – namely, that the highest degree of mnemonic efficiency is exhibited by techniques involving topographical arrangements of mental images (loci et imagines). As Richard Bolt states: "Intrinsic to the ensemble of studies outlined in the proposal was a study recalling the ancient principle of using spatial cueing as an aid to performance and memory." He called it the "Simonides Effect"[11] , alluding to the Greek poet Simonides of Keos, to whom the Roman rhetoricians attributed the invention of the ancient art of memory. The Macintosh User Interface is, as Nicholas Negroponte has implied, also based on this sort of Simonides Effect.[12]

It is true that the Human Interface Guidelines,[13] which were developed by Apple's Human Interface Group during the eighties, could well have been borrowed from the traditional teachings of rhetorical ars memoria. In addition to the basic "See-and-Point" principle, which recalls the ancient loci et imagines, the most important key words in the Guidelines are "Feedback and Dialogue", "Consistency" and "Perceived Stability". In the Rhetorica Ad Herennium we read that rote learning is most effective "when we [employ] not mute and indistinct images, but rather ones that set something in motion" (Apple's "Feedback and Dialogue"); these actuating images (imagines agentes) must be "arranged at certain fixed locations" (Apple's "Consistency"); and finally, says the Rhetorica, there must be no opportunity for us to "accidentally be mistaken in the number of locations" (Apple's "Perceived Stability").[14] Psychological studies in the workplace have confirmed that these principles considerably increase the ease with which the use of operating systems and software applications is learned.[15]

It is evident that, considering the explosion in user-designated storage options, the particular architecture of memory suggested by the desktop metaphor will have been put out of joint. And if we stick to the terms of our historical analogy, we might say that the current situation corresponds to the phase in which the classical memory palaces of antiquity gradually collapsed under the pressure of increasing amounts of amassed knowledge.

This is precisely the situation in which Camillo found himself with regard to the scholastic treatises of the Middle Ages: They curbed the remnant of a productive imagination in images from the memory in favour of a mechanical rote learning of prayers, virtues, and lists of mental objects.[16] It is here that Camillo comes in with his attempt to reanimate the now mechanical and uncreative memoria. He reminded his contemporaries that the function of imagines agentes was not just the "painting of an entire scene”,[17] but rather the stimulation of imagination through their agency. Camillo expressly emphasizes the matter that concerns him: "to find, in these seven comprehensive and diverse units, an order that keeps the mind keen and shakes up the memory."[18]

So these images from the memory were no longer purely a means of better remembering, but a medium for better concentration to the benefit of empathic recollection. For this purpose, he transplanted the arena of ars memoria from the traditional treasuries (thesauri) and palaces of memory to the Vitruvian theatre. The "drama" that he produced on this stage made use of the teachings of antiquity, but dressed them up in hermetic, cabbalistic costume.

But Camillo also departed from the tradition in one other aspect, in that he reversed the topography of structure of neo-classical theatre. With this inversion, the efficiency of the ancient architecture of memory could be significantly increased. Its user could navigate through the three-dimensional arrangement of his own will and vary his view between near and far accordingly.

No doubt there is a structural affinity between such ideas and the digital theater of memory. For some years now, there has been work on 3D visualisation processes: vector-driven cartographies such as Hyper-G, VRML, Hyperbolic Tree, Hotsauce, Flythrough, etc., which alter the depicted space with every movement of the mouse, joy stick or data glove. Such means are also used to attempt to increase the number of memory locations without creating disorientation.

But how is this related to the cosmological context in which these ideas were valid? Is this not entirely different from the post-metaphysical situation of memory architecture? Remarkably enough the opposite is true, because today's technology produces similar effects: The "Pan-Mnemism"[19] of our time is nourished by the dream of a universal, encyclopaedic machine. The hypertext guru Ted Nelson, for example, has something comparable in mind:

"Universal or grand hypertext […] means […] an accessible great universe of linked documents and graphics […]. This is an idea many people now share – the idea that we can get to everything, add to everything, keep track of everything, tie everything together, that we can have it all."[20]

What is at stake here is no longer merely the retrieval of profane information, the functional organization and recall of locations in the memory, but the spellbinding attraction of a fantasy of omnipotence: having the sum total of the world's knowledge at one's disposal – a move that his patron, the King of France, surely appreciated. And not only that: the spiritual inclinations of times past also make their reappearance in the digital theatre of memory. Brenda Laurel says:

"[...] for virtual reality to fulfill its highest potential, we must reinvent the sacred spaces where we collaborate with reality in order to transform it and ourselves."[21]

Now, it is in the nature of the dream of a total encyclopaedia that it must remain a dream. In this respect, it is worth noting that Camillo's Idea del Theatro was formulated in the future tense – as if the actual theatre of memory was still to be built. Unfinishability is here no shortcoming, but rather an added value; it does not diminish, but rather intensifies the mystery. The World Wide Web also owes its aura as a pan-mnemistic docuverse to the sfumato of a diffuse presentation of data, whose incompleteness stimulates us to act on hunches and intuitions, and thus produces that feeling of exuberant spatial experience with which passionate web-surfers are filled. The necessarily limited frame of the monitor only augments this experience by its peephole effect; it feeds the voyeuristic fantasy that there is still something infinitely more thrilling to discover than what is actually before one's eyes.

Nevertheless, what differentiates Camillo from today's cybernauts and sheds light on the possibly untapped potential of the digital theater of memory is the fact that his data construction always appears as theatre. The sites and images of his model are not meant to fascinate in an unmediated way, but should rather be reflected on as staged objects.

In contrast, the technical #movement# of images by means of computer animation does not lead to #an activity of# reflection but is perceived passively, in a reflex-like manner; instead of shaking up the memory, it conditions it. Camillo's theatre presents itself as an enclosed space, and, precisely for that reason, incites one to transcend it. On the other hand, the forms of 3D visualization, which give the illusion of endless space, prevent the data-traveller from realizing that the trajectory of his transit is fixed and thus undermine the desire for transcendence. This is because our imaginative activity diminishes in direct proportion to increased activity on the screen.

What is decisive to this difference is not the outer but the inner movement. In computer animation it is directed unambiguously at the consumption of an object; in Camillo’s work, however, the self-reflexive contemplation of the object by a subject also involves a rebound movement back to the subject. This reflexivity is made evident in Camillo's inversion of the theatre structure, which places the objects of memory in the tiers, where they simultaneously return the gaze of the observer while he stands on the stage and constitutes the centre of intellectual activity.

But why would this turnaround not also make Camillo's memory theatre a viable model for turning the digital staging of information into a self-reflective form?

Indeed, in recent years, there have been several artistic attempts to play upon Camillo’s idea. They indicate that an anamnesis of computer-presented data is not encouraged when the interface vanishes, as if it disappeared by immersion under the surface of the water, as is postulated by today’s pioneers of Interface Design, but rather, on the contrary, when the surface is mirrored back to the observer.

Once again, the idea for this comes from Yates’ #study#. Robert Edgar drew Bill Viola’s attention to the book and from then on Viola proclaimed Camillo the forerunner of digital ‘data space’.[22] It was on this basis that he produced his spatial installation ‘Theatre of Memory’ (1985), in which the processes of electrical connection in human memory are associated with the electronics of video. In the same year, Robert Edgar himself programmed his ‘Memory Theatre One’ on an ‘Apple II’, which used the then modest possibilities of computer graphics to reconstruct Camillo’s amphitheatrical data architecture. In the mid-nineties, Agnes Hegedus read this influential book together with her partner Jeffrey Shaw. She constructed a ‘Memory Theatre VR’ (1997), which used the new possibilities of computer simulation. On the inside walls of an accessible rotunda, which acted as a sort of ‘cave’, mobile panoramic images concerning the history of artificial memory were projected using a 3D mouse. And since 1998, the performance artist Emil Hvratin has carried out several projects in which the information scenarios of our era are questioned on the basis of Camillo’s work.

What do we learn from these reflections on the state of the computer age? To what extent do they give us a definite answer about the way information will be staged in the future?

As stated at the beginning, the Idea del Theatro is #has?# left much in the dark. Its "revelation" begins with a reference to the significance of silence in the face of divine secrets. And no doubt, Camillo's mystique only profited from the fact that he divulged just bits and pieces of information about how his theatre was made. Only as long as he continued to work on its expansion, to endeavour constantly to overhaul its architecture and iconology, could he have given himself and others the feeling of being on the trail of the secret of the alchemistic transformation of memory into recollection.

[1] Bolzoni, Lina: Il Teatro della Memoria; television film, 1990.

[2] Comp. the annotated list of links under www.sfb-performativ.de/seiten/b7_links.html.

[3] Frances Yates, The Art of Memory, London, 1996, p. 114 ff.

[4] Eco, Umberto: review of: Mario Turello, Daniele Cortolezzis: Anima Artificiale. Il Teatro magico di Giulio Camillo. in: L’Espresso, 14.8.1988.

[5] Bolzoni, Lina: The Play of Images. The Art of Memory from its Origins to the Seventeenth Century, in: Corsi, Pietro (ed.): The Enchanted Loom. Chapters in the History of Neuroscience, New York/Oxford, 1991, p. 23.

[6] Winkler, Hartmut [1994]: Medien - Speicher - Gedächtnis. Online: www.uni-paderborn.de/~winkler/gedacht.html.

[7] Davis, Stephen Boyd [1996]: The Design of Virtual Environments with particular reference to VRML. Online: www.man.ac.uk/MVC/SIMA/vrml_design/title.html.

[8] Cf. Bernard J. Baars, Das Schauspiel des Denkens, Stuttgart, 1998.

[9] Brenda Laurel: Computers as Theatre; Reading (Mass.) 1991.

[10] Richard A. Bolt: Spatial Data Management; Cambridge (Mass.) 1979, p.13.

[11] Ibid. 8.

[12] Nicholas Negroponte, Total digital. Die Welt zwischen 0 und 1 oder Die Zukunft der Kommunikation, Munich, 1995, p. 135 ff.

[13] Apple Computer Inc., Human Interface Guidelines: The Apple Desktop Interface, Reading (Mass.), 1987.

[14] Rhetorica Ad Herrenium III, XVIIf., Apple Computer p. 3 ff.

[15] Cf., e.g., Alexandra Altmann, "Direkte Manipulation: Empirische Befunde zum Einfluß der Benutzeroberfläche auf die Erlernbarkeit von Textsystemen," A&O: Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie 3 (1987): pp. 108-114.

[16] Cf. Frances Yates, The Art of Memory, London, 1966, p. 114ff.This does not contradict Horst Wenzel's observations on the participatory character of mediaeval memoria in: Horst Wenzel, Hören und Sehen. Schrift und Bild. Kultur und Gedächtnis im Mittelalter, Munich, 1995.

[17] Willhelm Schmidt-Biggeman, "Robert Fludds Theatrum memoriae," Ars memorativa. Zur kulturgeschichtlichen Bedeutung der Gedächtniskunst 1400-1750, eds. Jörg Jochen Berns and Wolfgang Neuber [Tübingen, 1993] p. 157.

[18] "la memoria percossa": 1550, p. 11.

[19] Elisabeth von Samsonow, "Zeit bei Giordano Bruno oder: Zum Verhältnis von Kosmochronie und Mnemochronie," eds. Eric Alliez et al., Metamorphosen der Zeit , Munich, 1999, p. 140.

[20] Cited in: Robert E. Horn, Mapping Hypertext: Analysis, Linkage, and Display of Knowledge for the Next Generation of On-Line Text and Graphics, Waltham, 1989, p. 259.

[21] Laurel, ibid. p. 196 ff.

[22] Bill Viola [1983]: Will There be Condominiums in Data Space? In: Ders.: Reasons for Knocking at an Empty House, London, 1995, pp. 98-111.

2012/10/25

Desire for the Invisible

"The true life is absent." But we are in the world. Metaphysics arises and is maintained in this alibi. It is turned toward the "elsewhere" and the "otherwise" and the "other." For in the most general form it has assumed in the history of thought it appears as a movement going forth from a world that is familiar to us, whatever be the yet unknown lands that bound it or that it hides from view, from an "at home" ["chez soi"]* which we inhabit, toward an alien outside-of-oneself [hors-de-soi], toward a yonder.

The term of this movement, the elsewhere or the other, is called other in an eminent sense. No journey, no change of climate or of scenery could satisfy the desire bent toward it. The other metaphysically desired is not "other" like the bread I eat, the land in which I dwell, the landscape I contemplate, like, sometimes, myself for myself, this "I," that "other." I can "feed" on these realities and to a very great extent satisfy myself, as though I had simply been lacking them. Their alterity is thereby reabsorbed into my own identity as a thinker or a possessor. The metaphysical desire tends toward something else entirely, toward the absolutely other. The customary analysis of desire can not explain away its singular pretension. As commonly interpreted need would be at the basis of desire; desire would characterize a being indigent and incomplete or fallen from its past grandeur. It would coincide with the consciousness of what has been lost; it would be essentially a nostalgia, a longing for return. But thus it would not even suspect what the veritably other is. The metaphysical desire does not long to return, for it is desire for a land not of our birth, for a land foreign to every nature, which has not been our fatherland and to which we shall never betake ourselves. The metaphysical desire does not rest upon any prior kinship. It is a desire that can not be satisfied. For we speak lightly of desires satisfied, or of sexual needs, or even of moral and religious needs. Love itself is thus taken to be the satisfaction of a sublime hunger. If this language is possible it is because most of our desires and love too are not pure. The desires one can satisfy resemble metaphysical desire only in the deceptions of satisfaction or in the exasperation of non-satisfaction and desire which constitutes voluptuosity itself. The metaphysical desire has another intention; it desires beyond everything that can simply complete it. It is like goodness—the Desired does not fulfill it, but deepens it.

It is a generosity nourished by the Desired, and thus a relationship that is not the disappearance of distance, not a bringing together, or—to circumscribe more closely the essence of generosity and of goodness—a relationship whose positivity comes from remoteness, from separation, for it nourishes itself, one might say, with its hunger. This remoteness is radical only if desire is not the possibility of anticipating the desirable, if it does not think it beforehand, if it goes toward it aimlessly, that is, as toward an absolute, unanticipatable alterity, as one goes forth unto death.

Desire is absolute if the desiring being is mortal and the Desired invisible. Invisibility does not denote an absence of relation; it implies relations with what is not given, of which there is no idea. Vision is an adequation of the idea with the thing, a comprehension that encompasses.

Non-adequation does not denote a simple negation or an obscurity of the idea, but—beyond the light and the night, beyond the knowledge measuring beings—the inordinateness of Desire. Desire is desire for the absolutely other. Besides the hunger one satisfies, the thirst one quenches, and the senses one allays, metaphysics desires the other beyond satisfactions, where no gesture by the body to diminish the aspiration is possible, where it is not possible to sketch out any known caress nor invent any new caress. A desire without satisfaction which, precisely, understands [entend] the remoteness, the alterity, and the exteriority of the other. For Desire this alterity, non-adequate to the idea, has a meaning. It is understood as the alterity of the Other and of the Most-High. The very dimension of height1 is opened up by metaphysical Desire. That this height is no longer the heavens but the Invisible is the very elevation of height and its nobility. To die for the invisible—this is metaphysics. This does not mean that desire can dispense with acts. But these acts are neither consumption, nor caress, nor liturgy.

Demented pretension to the invisible, when the acute experience of the human in the twentieth century teaches that the thoughts of men are borne by needs which explain society and history, that hunger and fear can prevail over every human resistance and every freedom! There is no question of doubting this human misery, this dominion the things and the wicked exercise over man, this animality. But to be a man is to know that this is so. Freedom consists in knowing that freedom is in peril. But to know or to be conscious is to have time to avoid and forestall the instant of inhumanity. It is this perpetual postponing of the hour of treason—infinitesimal difference between man and non-man—that im- plies the disinterestedness of goodness, the desire of the absolutely other

or nobility, the dimension of metaphysics.

• "Chez soi'*—translating the Hegelian bei sich —will for Levinas express the original and concrete form in which an existent comes to exist "for itself." We shall (rather clumsily I) translate "chez soi" by "at home with oneself." But it

should be remembered that it is in the being "at home," i.e. in the act of inhabiting, that the circuit of the self arises.—Trans.

1

". . . in my opinion, that knowledge only which is of being and of the unseen can make the soul look upwards . . ." Plato, Republic, 529b. (Trans. B. Jowett, The Dialogues of Plato, New York, 1937.)

(Totality & Infinity by Emmanuel Levinas)

2012/10/24

2012/09/11

2012/08/21

2012/08/01

je crois que j'avais

entre 29 et 30 ans. J'étais en prison. Donc,

c'était en 39, 1939. J'étais seul au cachot, en cellule enfin. D'abord,

je dois dire que je n'avais rien écrit sauf des lettres à des amis, des

amies et je pense que les lettres étaient très coneventionelles,

c'est-a-dire des phrases toutes faites, entendues, lues. J'amais

éprouvées. Et puis, j'ait envoyé une carte de Noel à une amie Allemand

qui était en Tchecoslovaquie. Je l'avais achetée dans la prison et le

dos de la carte, la partie réservée a la correspondance était grenue. Et

ce grain m'avait beaucoup touché. Et au lieu de parler de la fête de

Noel, j'ai parlé du grenu de la carte postale, et de la neige que ca

évoquait. J'ait commencé à ecrire à partir de là. Je crois que c'est le

déclic. C'est le déclic enregistrable.

Jean Genet

Jean Genet

2012/07/26

2012/07/12

2012/07/07

2012/06/26

the world beneath the city

the slimy thing in the middle that looks like an organ is a colony of tubifex worms in the sewer of north carolina. the couple further downwards is living in tunnels underneath las vegas with about 1000 other homeless people on a wet floor. the last picture is the beginning of the teenage mutant ninja turtles.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)